Experience the Story Behind Waikīkī’s Healer Stones of Kapaemahu

The new Bishop Museum exhibit explains why the history of the stones remained suppressed for decades.

by Robbie Dingeman – Honolulu Magazine – June 30, 2022

The fascinating and complicated story of the Healer Stones of Kapaemahu can be experienced now through October in a sprawling bilingual exhibit at the Bishop Museum that explores themes of culture, healing and inclusion.

Hidden in plain sight, the Healer Stones of Kapaemahu—four large volcanic pōhaku—rest in one of the busiest parts of touristy Waikīkī—near the police substation and the statue of Duke Kahanamoku—yet if you read the plaque that marks the spot, you’ll find some of the history has been repressed for decades.

According to Hawaiian mo‘olelo, four healers arrived from afar, perhaps Tahiti, and settled in Waikīkī, where they used their healing arts to help others. The legend says that the four were māhū. Exhibition Curator Hinaleimoana Wong-Kalu explains: “Māhū is understood as that space between kāne and wāhine, between male or female.” She adds: “What makes us unique is that we have elements of male and female perspective, emotion, and spirituality as well as our spirit, our heart, our mind.”

The exhibit depicts the gentle legendary healers who settled in Waikīkī sharing miraculous cures with the people. After a time, the story says that the healers transferred their names and spiritual powers to the stones, then vanished. And the monumental stones remained on the beach for centuries, memorializing their good work, the exhibit notes in both English and Ni‘ihau Hawaiian.

Wong-Kalu, who is fluent in Olelo Niihau—which doesn’t use diacritics while our magazine style does—says the exhibit that opened in June grapples with crucial themes. “Hawaiian culture had a place for māhū. And māhū was a term that was weaponized against me and people like me. I grew up thinking it was a bad word. I grew up thinking it was something to avoid and I resented that and I grew to hate that,” she says.

As years went by and attitudes changed, Wong-Kalu found that being māhū was a source of great empowerment: “People who are māhū are ones who have been great caretakers, great healers, great repositories of knowledge and history, language, culture, here in Hawai‘i and throughout the Pacific.”

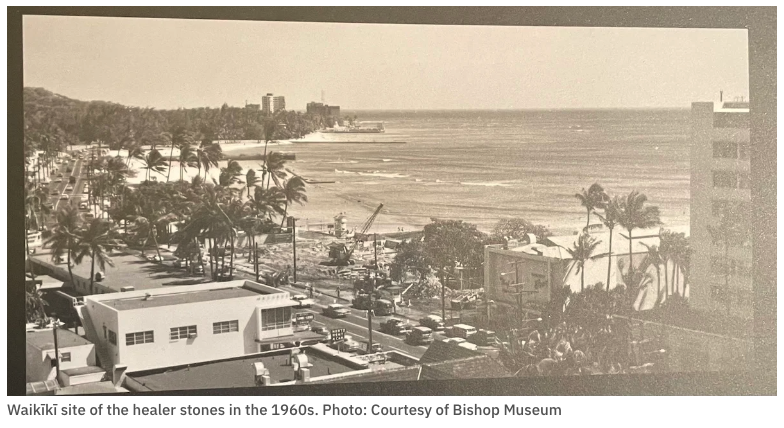

By the early 1900s the stones were on the beachfront property of Archibald Cleghorn who preserved them. After he died, modernization and militarization brought many changes, and in 1941, the stones were buried under a bowling alley built on the property, says DeSoto Brown, Bishop Museum Historian and Curator of the Archives. He says the City and County condemned the shorefront stretch for public use in 1958 and the bowling alley was demolished in 1963. Then Hawaiian elders, including scholar Mary Kawena Pukui, called for restoration of the once-revered stones.

Yet when the stones’ plaque was updated, in 1963 and 1997, it left out the māhū identification of the healers, of their acceptance and inclusion, to avoid controversy.

Brown says this exhibit recognizes the treatment of transgender people globally, in cases where they were shunned, accepted and, in some cases, they had special or superior status. He says these themes remain relevant in a world where gender issues can still be fraught. “One of the reasons we want to talk about this and put it forth is to say this is the reality of what was happening,” Brown says.

The Healer Stones of Kapaemahu exhibit runs through Oct. 16.

In addition to a three-dimensional model of the stones and dramatic artwork gleaned from the Kapaemahu film, the exhibit includes a powerful timeline of Hawaiian history, when the legend was first published in 1907, and more recent accounts of suppression of gender differences in discrimination against those in the LGBTQ community as well as the emotional battle to legalize same-sex marriage. One room of the exhibit reflects on The Glade Nightclub, a well-known nightspot of the ’60s and ’70s in Chinatown where māhū performers won fame, a paycheck and a community.

The legend also is told in an eight-minute version of Kapaemahu on continuous display, directed by exhibition co-curators Dean Hamer, Joe Wilson and Wong-Kalu. The team also just released a new kids’ book of the same title in both Niihau Hawaiian and English.

Even how the stones got to their beachfront home remains shrouded in mystery, says Brown. “Waikīkī geologically doesn’t have big basalt stones because of the way it formed.” And that meant they had to be transported from Kaimukī by people 500 or more years ago. “And that itself is a huge task, and this is ancient Hawaiians, they have no carts, they have no wheels, they have no animals,” he says. And another piece to the enigmatic history.

1525 Bernice St., (808) 847-3511, open daily, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., closed Thanksgiving and Christmas days, bishopmuseum.org

General Admission adults: $24.95; Hawai‘i residents, Hawai‘i college students & military with ID adults: $14.95; seniors (65-plus): $21.95; resident and military seniors (65-plus): $12.95; youth (4–17): $16.95; resident and military youth (4–17): $10.95; children (3 and under): free; children age 16 and younger must be accompanied by an adult.